How to Steal an Army

On the mechanics of Mao's rise to power in Jung Chang and Jon Halliday’s “Mao: The Unknown Story.”

“We love sailing on a sea of upheavals. To go from life to death is to experience the greatest upheaval. Isn’t it magnificent!” wrote a young Mao Zedong1 in his college notes. Destruction, he asserted, must always come before change. China must be “destroyed and then re-formed … This applies to the country, to the nation, and to mankind.” Loathe to stop at the earth, Mao suggested the universe itself should welcome its destruction: “People like me long for its destruction, because when the old universe is destroyed, a new universe will be formed. Isn’t that better!”

Much later in life, Mao would continue to express this same worldview. When one time on a mountain walk Mao saw a house burning in the distance, he exclaimed: “Good fire. It’s good to burn down, good to burn down!” Seeing the shock on the face of the photographer who was with him on his walk, Mao explained: “Without the fire, they will have to go on living in a thatched hut.” For Mao, the old was not something to be cultivated and developed, but destroyed and replaced.

But there was also something else that Mao revealed in his college writings. “People like me only have a duty to ourselves; we have no duty to other people,” wrote the young Übermensch. “Of course there are people and objects in the world, but they are all there only for me.” The notion of duty or of building something greater than oneself held no appeal for him. “A good name after death cannot bring me any joy, because it belongs to the future and not to my own reality … I have my desire and act on it.” Many years later, in a 1970 interview with Edgar Snow, Mao described himself as “a man without law or limit.” Mao had no use for legislation, or indeed any external forms of authority. He ruled by dictates and five year plans.

Jung Chang and Jon Halliday’s Mao: The Unknown Story is an uncensored look at Mao’s rise to power, the civil war against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, the terror and purges of Yenan and the tragedy of his superpower program, culminating in the disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. It’s an incredible read which presents an unvarnished account of the events, the details of most of which remain unclear to this day, obstructed in large part by Mao revising the facts to create his own narrative.

What I found especially fascinating was the mechanics of Mao’s seizure of power. As a dictator, Mao differed from a Hitler or a Mussolini in one key way: he was devoid of charisma. He hardly ever gave public speeches, and when he did, they were lackluster affairs. The way he obtained power was not by attracting the support of the public or even his cadres, but by a ruthlessly cunning series of stratagems that gathered existing sources of power into his hands. Quite incredibly, he stole command over armies. Those who stood in his way were sometimes bribed, more often blackmailed, and most often eliminated. Those who failed to support him were all purged. One of Machiavelli’s precepts for a ruler is that “it is better to be feared than to be loved, if one cannot be both.” Mao could not be both.

I. The Purse

At an emergency meeting in 1927, Mao uttered the now famous remark that “power comes out of the barrel of the gun.” This would be true for most of his reign. But early on in his career, Mao identified and tapped into a different source of power.

In the early 1920s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was actually one of at least 7 other communist parties, with one boasting over 11,000 members. Unlike the others, however, the CCP was picked by Moscow as the vehicle for infiltrating China and influencing its future political development. It was not merely a case of support—in the early days, the CCP was essentially Moscow’s project. In 1922, over 94% of CC’s expenditure came from Russia.2 With its hold over the purse strings, Moscow could dictate CCP’s policies and pick its cadres. The meddling was so intrusive that the party’s co-founder, Chen Tu-hsiu, would openly rage about it. “If we take their money, we have to take their orders,” he warned. When the money was inevitably taken, he would shout: “Do we have to be controlled like this? It simply isn’t worth it!” But as it turned out, this foreign money was absolutely essential, and would remain essential until CCP’s eventual triumph over the Nationalists. Without this funding, all the other communist parties collapsed.

In 1920, Mao got in touch with Chen Tu-hsiu. This “bright star in the world of thought,” as Mao called him in an article, had just founded the CCP. Flattery did the trick, and Chen gave him a job as a bookseller in Changsha, tasked with promoting Party literature. When the party organized its first congress in Shanghai the following year, Mao was invited as one of the delegates and given 200 yuan to cover his expenses—a sum that was over twice his annual salary as a teacher. Further Party salary increases soon followed, allowing Mao to quit his teaching and journalism jobs and focus wholly on politics.

Mao did not speak much at the first congress. Instead, he stood back and observed. And what he saw was very instructive. The man who chaired the congress, Chang Kuo-tao, was chosen because he had been to Russia and therefore had their trust. When the Russians did not agree with a resolution that passed the previous day, Chang simply proposed cancelling it. As long as the CCP depended on Moscow’s money, arms and training, Moscow had the final say.

From then on right until Mao attained supreme power, whenever Mao spoke with the Russians, he would wear a mask of obsequiousness, employing words of absolute deference. When some Russian Comintern members proposed attacking Changsha in an early campaign, Mao said the order made him “jump for joy three hundred times.” Another time, when Stalin sent a film-maker to make a documentary of Mao, Mao posed with a text by Stalin in his hands, the dictator’s portrait prominently visible on the cover. Mao told the film-maker that Russia was the only country he wanted to visit, because he dreamed of meeting Stalin. “With what warmth Mao talks of comrade Stalin!” the film-maker noted. The fawning was overt and excessive, but it worked. Whether or not the Russians believed his enthusiasm, it clearly positioned him as someone willing to work with Moscow and to modify his policies to accommodate it, especially in contrast with other members who wanted to take a more independent path. As a result, whenever there were disagreements between him and other CCP leaders, Moscow usually took his side.

II. The Gun

In September 1927, Mao stole an army.

He did it in a way that was both crafty and brazen. At the time, Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalists, launched an all out campaign against the Communists. Stalin told the CCP to form an army and start seizing territory. The Communists succeeded in organizing an uprising in Nanchang, in which 20,000 Nationalist troops switched sides over to the Reds. These troops were told to move south to the coast, where the Russians planned to supply them with arms.

Mao saw that the troops would have to pass through Hunan on their way south, so he proposed organizing a peasant uprising in south Hunan. Appealing to the ambitions of the CCP leaders, Mao painted a picture of a future massive Red base encompassing “at least five counties.” Once he had their attention, he made another request. A contingent of the mutineers would, of course, have to be detached and come help him do it. Shanghai—the CCP’s base of operations at the time—approved it. Forced to march in sweltering heat, desertions and disease begun taking their toll on the mutineers. The army was shrinking by the day. When Mao arrived in Changsha to meet Comintern representatives, he proposed that they “narrow down the uprising plan” and focus on Changsha alone. They agreed and made Mao head of a “Front Committee,” a position that gave him command over his detachment in the absence of any higher ranking Party members.

Instead of going to join the troops at Changsha, Mao went to Wenjiashi, a town 100 km to the east. Before the troops could attack Changsha, Mao told them to abandon the plan and come to him. But Mao did not stay in Wenjiashi. He led the detachment to a mountain range, 170 km south, a place with poor road access and no telegraph. There, he told his force of about 1,500 troops that they were going to be “mountain lords”—i.e. bandits. “Mountain Lords have never been wiped out, let alone us,” he assured his reluctant listeners. The isolated troops had no means of communicating with the Party HQ at Shanghai. Their only choice was whether to obey Mao or desert. Many deserted. In just a fortnight, Mao lost about half his men. He didn’t stop them, but he did take their weapons.

Still, however small, he now had his “barrel of the gun,” and he began to employ it right away. To get supplies, his force simply raided nearby counties. To prevent the troops feeling like bandits, the attacks were conducted under the ideological banner of da tu-hao—”smash landed tyrants”—but the range of those who could be classified as a “landed tyrant” could doubtless be expanded according to circumstances. This was also the time when Mao began to practice terror by staging public executions in the places he conquered. In one place, a county chief was tied to a wooden frame, and then killed by people thrusting spears into him. The executions were not only public, their viewing was made compulsory. Mao needed the people to understand who they were dealing with.

When Shanghai finally learned about what happened to their army, they immediately summoned Mao. When Mao failed to comply, Shanghai expelled him from his Party posts, telling the Hunan branch that the “army led by comrade Mao Zedong … has committed extremely serious errors politically.” The HQ then ordered Hunan to send a senior Party member to “reform the Party organization there,”—i.e. to get rid of Mao. By a stroke of luck (for Mao, at least), the whole of the Hunan committee was arrested by the Nationalists just a week after receiving the instructions. Months later, in March 1928, an envoy finally reached Mao. Mao was told to step down. No problem. Mao pretended to resign by giving his position to a puppet, while assigning himself the title of “Division Commander,” thus retaining full control of the army.

In April 1928, Mao stole another army.

The rest of the Nanchang mutineers, about 4,000 men, led by a 41-year-old officer called Zhu De, sought refuge in his base. They were on the run from Nationalist forces after a string of botched uprisings, wherein under such slogans as “Burn, burn, burn! Kill, kill, kill!” his forces brought death and destruction to Chenzhou and Leiyang. Instead of converting the populace to their cause, the burning and the killing provoked the populace to revolt against the Communists. The Nationalists, who now had the support of the locals, drove Zhu out.

Despite the fact that Zhu’s army outnumbered Mao’s 4 to 1, Mao realized that he could gain control over his troops by merging the two armies into one and splitting the political and military responsibilities between the two leaders. And, because the political outranked the military, by giving himself the role of the Party commissar, Mao would get the final say. He requested Shanghai’s permission to form a “Special Committee.” Not waiting for their reply, he went ahead and immediately announced a rally to celebrate the unification of the two armies into what he now called the “Zhu-Mao Red Army.” Mao then organized his own congress (filled, of course, with his own delegates), which made him head of a Special Committee, and Zhu the commander of the army. Shanghai did end up approving this move, after consulting Moscow. Stalin, who got personally involved in the matter, decided to back Mao as he had the two qualities Stalin was looking for: deference to Moscow and unwavering ruthlessness. “Insubordinate, but a winner,” he later called him.

Once he had Shanghai’s blessing, Mao proceeded to brazenly abolished Zhu’s position, seizing the role of the commander for himself. He did not ask Shanghai. He did not even inform them when he did it. It was only four months later, when he sent Shanghai a 14-point report, did he let them know that “the Army”, finding itself “in a special situation,” had “decided temporarily to suspend” Zhu’s post. It was point 10 of the report.

III. Political Maneuvers

In June 1929, Mao’s army was taken from him.

Shanghai sent a man called An-gong to act as third in command. What he found shocked him. Mao, he said, was “forming his own system and disobeying the leadership.” He was, in An-gong’s words, “power-grabbing” and “dictatorial.” With the arrival of this new ally, Zhu, who was previously intimidated by Mao, found the courage to speak out and challenged his unauthorized dismissal. Together, they gathered enough support to organize a vote, and dismissed Mao as leader of the army. “I have a squad, and I will fight” threatened Mao. It was no use—his followers were disarmed before the vote.

Lacking charisma, the army provided Mao with his main means of influence: violence. Without the army, Mao was almost powerless. Almost. While Mao could not inspire and attract people, he possessed a deadly combination of ruthlessness and knowledge of human nature. From an early age, Mao understood people. He understood what drives them, what makes them do the things they do. When he was still very young, he would often argue with his father. One day, when his father began berating him in front of his guests, Mao called him names and stormed out of the house. His father ran after him, ordering him to return at once. When Mao reached a pond, he warned his father that he would throw himself into the pond and drown himself if he dared come any nearer. His father backed down. Mao laughed as he retold the story, adding: “Old men like him didn’t want to lose their sons. This is their weakness. I attacked at their weak point, and I won!”

Now, Mao sought to find the weak points of the troublesome comrades who dared to get in the way of his ascent. He discovered that Lin Biao, a commander of one of the army’s units, held a grudge against Zhu De. So Mao befriended him. Their friendship would last many years and would be very profitable for both of them (that is, until Lin grew too powerful for Mao’s liking and died in plane crash in his attempt to flee China). But Lin’s unit was not enough—Mao needed men of his own. He set off to Jiaoyang in the province of Fujian to, in his own words, “do some work with local civilians.” There, capitalizing on his reputation, he called a congress. When the fifty or so delegates arrived, he sent them away for a week to conduct “all sorts of investigations.” When they returned, they discovered that Mao was “ill,” so the congress was further delayed, and when it did open, the meetings stretched for weeks.

Eventually, with the threat of Jiaoyang coming under attack from the approaching Nationalist forces, the congress was closed. The delegates left. But Mao did not. He proceeded to assign key posts to his own men and made one of his cronies the head of the local Red Army division. These decisions were ascribed to the now vacant congress.

Collectively, Lin and Mao now had control of about 6,000 troops—half that of the “Zhu-Mao Army.” When Zhu ordered the army units to assemble on August 2, 1929, Mao’s and Lin’s forces did not come, forcing Zhu to fight the Nationalists on his own. Zhu now had a big problem. In the same way that Mao once took a stand against his father, threatening to end his life if he did not back off, Mao now took a stand against Zhu, threatening a deadly stalemate unless his control of the army was returned to him. It was going to be either Mao or Zhu. The party to make the decision was, as it often was in CCP’s early years, Moscow, or rather, Moscow’s operatives in Shanghai—a pair of European Communists from Germany and Poland, whom the Chinese called mao-zi, the “hairy ones,” due to the fact that they had more body hair than the Chinese. The “hairy ones” decided that Mao was correct to abolish Zhu De’s post and An-gong was recalled. Zhu De was forced to meekly write to Mao, “urging comrade Mao to return,” and when Mao did not return, they had to send soldiers to escort him formally. Mao won, and he was returning with the pomp of a victor.

Upon being reinstated, Mao took immediate steps to prevent what happened again by abolishing holding votes, labelling the practice “ultra-democracy.”

IV. The Chinese Soviet Republic

Having found a successful blueprint for seizing armies and conferences, Mao continued to apply it. In August 1930, Mao set off towards the second largest Red Army division, which was under the command of Peng De-huai. He messaged Peng, saying he was on the way to “help” him. A surprised Peng replied that he did not need any help. Unperturbed, Mao send him another message. This time it said that he needed help, asking Peng to come to him instead. The moment Peng arrived, he found his division integrated into Mao’s army, and himself demoted to a deputy commander under Zhu De.

Likewise, Mao again repeated his stratagem of hijacking conferences, but this time he shifted a conference forward rather than delaying it. A “joint conference” was announced at Jiangxi, to be held on the 10th of February. But then the conference was shifted forward to the 6th, and when the delegates arrived four days later, they discovered that the conference was already over. Once again, Mao filled key positions with his own men. When the disgruntled delegates began to complain, he resorted to terror, executing key leaders as “counter-revolutionaries.”

Mao faced substantial resistance. To suppress it, he resorted to purges and terror, which carried on in various degrees throughout his life, limited perhaps only by how far his cronies were capable of going at the time. To initiate a purge, Mao’s opponents, or those suspected of being so, were branded “AB,” meaning “Anti-Bolshevik.” When the Reds at Jiangxi rebelled against Mao’s brazen takeover, he accused them of being filled with AB agents. “Without a thorough purge of the kulak3 leaders and of the AB … there is no way the Party can be saved,” he said. A vicious man by the name of Lie Shau-joe was put in charge of the proceedings. His men would simply say “You have AB among you,” and begin arresting and torturing people until they gave them names. Those people were in turn arrested and tortured until they confessed. Mao brushed aside any criticisms of torture resulting in false confessions. “How could loyal revolutionaries possible make false confessions to incriminate other comrades?” he asked. Worse still, failure to participate in the purge condemned you as AB. “Any place that does not arrest and slaughter, members of the Party and government of that area must be AB, and you can simply seize and deal with them.”

The CCP’s first great triumph was the founding of the Chinese Soviet Republic on November 7, 1931, which spanned across seven provinces around the Communists’ two major centers: Red Jianxi and Red Fujian. For Mao, it turned out to be a major setback. The problem was that while Mao was appointed head of state—or, more precisely, the chairman of the Central Executive Committee—the command of the army was, again, given to Zhu De. Worse still, Chou En-lai, the competent organizer and diplomat, arrived from the Shanghai HQ in his capacity as Party boss. Not only was the army being pulled out of his hands again, Mao now had to deal directly with his official boss, a man who had monopoly over communications with Moscow.

When Chou first arrived, Mao took his chair and tried to hold the meeting as though he were still in command. He had to be removed from his seat. Soon afterwards, the Nationalists press published a “recantation notice” under Chou’s pseudonym, in which its author condemned the CCP and renounced communism. This was almost certainly a plant, but in the paranoid atmosphere of the 1930s, it was a serious threat to Chou’s authority. While there is no proof that Mao was responsible for the notice, this threat of blackmail helped him push Chou towards ruling in his favor in a crisis meeting in March 1932. When the other leaders proposed focusing their forces westwards, Mao insisted on going in a completely opposite direction. Unable to change Mao’s mind, Chou split the army, giving Mao more than half of the troops. Once Mao had command of the troops, he did not even go to where he first proposed, but took over a weakly protected city of Zhangzhou. He capitalized on this victory to raise his profile abroad, particularly in Moscow. More important, Mao looted the city. A truck filled with gold, silver and jewels was marked: “To be delivered to Mao Zedong personally.” Mash stashed the loot in a cave—insurance for a rainy day.

Mao’s insubordination did not go unnoticed. Party leaders, including Chou En-lai, complained to Moscow. Unfortunately for them, as Mao’s recent victories have elevated his image on the world stage, Moscow did not want to see him removed. They advised conciliation. “Mao Zedong is already a high-profile leader … And so … we have protested against Mao’s removal,” said Moscow’s representative in Shanghai. Encouraged, Mao continued disobeying party orders, refusing in the summer of 1932 to defend two bases under attack from Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. This was too much. The CCP convened an emergency meeting in October, in which Mao was denounced for “disrespect for Party leadership, and lacking the concept of the Organization.” Without asking Moscow, they dismissed Mao from his army post. To explain their actions to Moscow, they said that, “owning to sickness,” Mao was stepping down from his military role.

This was a major setback, and it would take all of Mao’s ruthlessness and cunning to claw his way back up to the top.

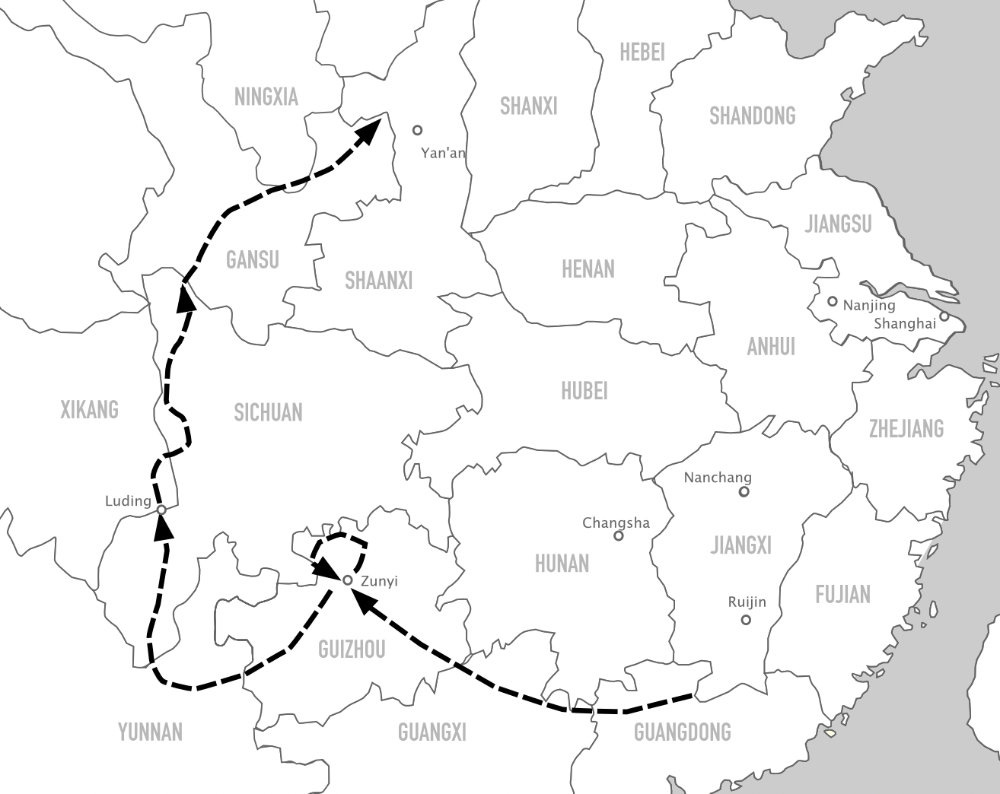

V. The Long March

Much mythologized by the CCP, Chángzhēng, commonly translated as the “The Long March,” was a year long trek across China. It began with the failure of the Chinese Soviet Republic to withstand the advance of the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek. The Nationalists had spent months building roads and constructing a network of fortifications in an ever closer proximity to the Red bases. As the Red Army was also outnumbered 10 to 1 by Kai-shek, this methodical and carefully planned approach was unstoppable. The Communists had to retreat.

One of Mao’s rivals who had recently risen to the top, Po Ku, suggested that, since Mao was head of state, he should be left behind. Understanding the danger he was in, Mao dropped his hostility and went directly to Po, promising to bury his past disagreements. In an instant, Mao transformed himself from an uncooperative rival to a helpful comrade. A companion of Lin Biao’s who saw Mao at the time observed that “instead of being engaged in factional activities on the sly,” he was now, “very disciplined.” More important, he delivered the stash of loot from Zhangzhou—funds that the Party desperately needed for their long journey ahead. This was enough to sway Po. In October of 1934, about 80,000 people set off on the Long March.

Immediately, Mao began forming alliances. Out of the seven members of the Secretariat—the executive body of the CCP—only four were on the march: Po Ku, Chou En-lai, Lo Fu and Chen Yun. The last of these, Chen Yun, took no interest in politics and was often absent, choosing to focus on logistics. Just as Mao had befriended Lin Biao in 1929 when command of the army was ripped out of his hands and given to Zhu, so now he befriended Lo Fu by once more exploiting a grudge against his colleague: Po Ku. That left Chou En-lai and Po Ku. Mao and Lo Fu came up with a plan on how to turn Chou against Po, and get Lo to take over Po’s position as party boss.

Together with another one of his allies, Wang Jia-xiang, known as the Red Prof, Mao and Lo called for a post-mortem to establish the reasons for the loss of the Chinese Soviet Republic. This was a reasonable request, and Po Ku did not object. At the meetings held in the middle of January 1935, the trio blamed Po Ku for the disaster. Their attack did not wholly succeed, as the meeting failed to reach consensus, but Mao did achieve one very important thing: he got a seat on the Secretariat.

Lo Fu got himself the job of putting together a report to be sent to Moscow on the reasons for the loss of the Red state. Lo Fu’s first draft was titled: “Review of military policy errors of Comrades Po Ku, Chou En-lai and Otto Braun.” The last of these, Braun, was a foreigner, and so provided a convenient scapegoat. Naming Chou En-lai in the report, however, was overt blackmail. He had to decide: either he would go to Mao’s camp, or face reputational damage. In Braun’s words, Chou “subtly distanced himself from Po Ku and me, thus providing Mao with the desired pretext to focus his attack on us while sparing him.” Chou chose Mao, and Lo Fu dropped his name from the report. With the majority vote of the Secretariat under his control, Mao and Lo immediately dismissed Po Ku from his post and put Lo Fu in his place. The coup was so brazen that the conspirators decided to keep it secret from both the Party and the army for weeks so as to not risk a rebellion.

As the army made its way west through Guangxi and Guizhou, Mao faced what was perhaps his greatest obstacle. North west lay Sichuan province, where they were to link up with a man called Chang Kuo-tao and his Red Army force of 80,000 men. Not only was Chang’s army more than twice the size of Mao’s, he was as ruthless and ambitious as Mao himself. Linking up with him, especially right after carrying out an underhanded coup would be very dangerous. Being in a stronger position, Chang could easily side with Po, and Mao and his co-conspirators could face retribution.

So Mao and Lo delayed. On January 22, 1935, Mao cabled Chang, telling him to move to the south of Sichuan to wait for them. But just days later, he proposed turning around and setting up an ambush for the pursuing Nationalist troops. The ambush turned out to be disastrous, and on the 28th, the Reds suffered their biggest defeat on the Long March, costing them 10% of their force, with around 4,000 killed or wounded. Mao and Lo then argued that it was far too dangerous to continue, and that they should set up a temporary base in Guizhou. Despite facing strong resistance, the leaders agreed to stay. On February 27, they captured Zunyi. This victory gave the conspirators conditions favorable enough to finally announce the fact that Po Ku had been replaced by Lo Fu. As there was no unrest, Lo Fu created a new military post just for Mao: “General Front Commander.”

For the next couple of months, Mao continued to delay the link up in order to solidify his control of the party. Instead of going to Sichuan, Mao’s army made pointless and disastrous attacks on the Nationalists, maneuvering their army in a way that left the Nationalists baffled. The Reds were, in Chiang Kai-shek’s words, “wandering in circles in this utterly futile place.” Finally, at the end of April, sensing that he reached the limit of his commanders’ patience, Mao allowed the army to move north into Sichuan. By the time he linked up with Chang Kuo-tao a couple of months later, his army was reduced to a shred: only 10,000 men remained. Chang’s army of 80,000 now outnumbered his 8 to 1. He had won the political battle for the control of the Party, but he now had to contend with the threat of pure violence.

As expected, Chang Kuo-tao demanded control of the army. Mao and his circle shot back, trying to exert pressure on Chang by criticizing his army from a political standpoint by calling his army “bandit style” (conveniently forgetting Mao’s own “mountain lords” episode). Chang’s men responded derisively: “How can such a Center and Mao Zedong lead us?” Worse, Mao’s rank-and-file began to vent their complaints, criticizing the leaders for being carried in sedan chairs while they had to march on foot. In response, they were told that “the leaders have a very hard life. Although they don’t walk, nor carry loads, their brains and everything have it much rougher than we do. We only walk and eat, we don’t have cares.” This response is almost straight out of Orwell’s Animal Farm. Having reserved the milk and apples for themselves, the pigs (representing the leadership) explained: “You do not imagine, I hope, that we pigs are doing this in a spirit of selfishness and privilege? Many of us actually dislike milk and apples. … Milk and apples … contain substances absolutely necessary to the well-being of a pig. We pigs are brainworkers.” [emphasis mine]

Mao could not stop Chang Kuo-tao taking control of the army. But he came up with a cunning way to get rid of him. The CCP’s immediate plan was to travel north to the border with Mongolia, a Soviet ally, to receive arms and other supplies. Mao suggested splitting up the force into two columns, with each traveling along a different route. Chang would take control of the Left Column, while Mao and the rest of the CCP leadership would travel with the Right Column. Chang did not seem to mind, perhaps because the route of the Left Column was more favorable. So they set off. But Chang underestimated Mao. Just nine days after the two columns set off on their alternative routes, Chang received a cable from Mao. In the name of the Politburo, he was ordered to turn his column around and follow the same route as Mao. When Chang tried to argue, Mao accused him of being “opportunist” for “choosing the road with fewest obstacles.” Chang turned around.

But there was a massive problem. The route Mao had taken was extremely dire. It was a swampland with no inhabitants, no food and no place for shelter. Dark fogs, hails and storms wore down the troops as they tried to make slow progress through the arduous terrain. People began to die of sickness and starvation. “When everything ran out, we ate the roots of grass and chewed leather belts,” recalled one soldier. On one hand, the route was disastrous. On the other hand, it was a perfect trap for Chang and his men. Mao urged him on by telling him that the route was “short in distance and plentiful in shelter.” To maximize the damage, he also advised him to bring the wounded and the sick. As expected, Chang could make no progress. Instead of risking his men’s lives, he called the journey off, postponing it until the following year.

The Right Column, with which Mao and the CCP leaders were traveling, also included Chang’s commanders and troops. Chang was officially the commander of the army, and his order to postpone the journey until next year would be obeyed by them. So Mao simply ran away with his own troops. In the middle of the night, select commanders were told to gather their troops and be ready to leave at once. As they decamped in the darkness, Mao’s men took with them radio communication equipment and detailed maps. In the morning, when Chang’s confused commanders woke up to find Mao and his entourage gone, they were informed that if they pursued, they would be fired upon. With a cunning stratagem, Mao jettisoned his greatest rival and rushed ahead to become the first one to make contact with the Russians. And, once he had the monopoly over the CCP’s communications with Moscow, there would be no second chances for Chang.

Mao’s destination was northern Shaanxi, where the small provincial town called Yenan would become the CCP’s capital for the next decade. There was already a sizable Red base in the area with around 5,000 troops, commanded by a man called Liu Chih-tan. The takeover would be quick and painful. As Mao approached the base, he noted that Chih-tan’s leadership “does not seem to be correct.” The local Party bureau with jurisdiction over the area was told to purge the base. Another Red Army unit of around 3,400 men, which arrived via a different route, was joined by Party representatives, and they began purging Chih-tan’s base, killing and torturing many of his men. Despite having more men, Chih-tan did not resist. He was arrested and condemned as a Nationalist spy. Upon arriving, Mao played the good cop and called the purge a “serious error.” Scapegoats were found and Chih-tan was released, although now conveniently relieved of command over his own base by being made a lowly commander of a small army unit. More conveniently, he soon died by being shot away from the action while on a special assignment by Mao.

In 1937, the Red Prof, went to Moscow for medical treatment, replacing Wang Ming as China’s representative there. The following year, when he was about to return, the Red Prof had a conversation with Georgi Dimitrov, the leader of the Comintern. In response to questions about party unity, Dimitrov told Wang that the CCP must work to resolve its problems “under the leadership headed by Mao Zedong.” When the Red Prof returned to China, Mao assembled the other CCP leaders “to hear the Comintern’s instructions,” using Dimitrov’s incidental remark to take control of the proceedings.

The years of the Second World War would be dominated by a massive terror campaign in Yenan, which Mao used to utterly annihilate not only any thoughts of resisting him, but any form of free thought in general, turning living beings into the cogs of an ideological machine (I will cover the mechanics of Mao’s terror campaign in my next post, as this is a subject that deserves special attention).

On the 23rd of April, 1945, Mao opened the 7th Congress of the CCP. He was voted chairman of the Central Committee, the Politburo and the Secretariat. His hold over the Party was now completely unassailable. “March Forward under the Banner of Mao Zedong!” said a massive banner above the stage. Mao had crushed every one of his rivals in the CCP and emerged the victor.

Mao did not inspire people or create institutions, rather, he tapped into existing power structures, seizing control by exploiting their bureaucratic machinery. His authority was not the authority of a visionary and effective leader, it was bestowed on him by an external hierarchy. The deficit of personal authority grew ever more apparent as time went on, for the higher he rose, the more violence he had to use to maintain his position. As Hannah Arendt wrote in On Violence: “Power and violence are opposites; where one rules absolutely, the other is absent.” Mao had no qualms about using absolute violence.

“What stands in the way becomes the way,” wrote the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations about two millennia ago. He was talking about self-perfection, about using obstacles as opportunities to exercise virtue and become a better human being. He was the most powerful man in the world, the ruler of an empire, yet his actions were directed by a selfless love for other people. Mao was the opposite. He cared only about himself. “People like me only have a duty to ourselves,” wrote the young Mao. For such a man, the same words assume a darker aspect. When in early 1940s, a writer for Liberation Daily, Wang Shi-wei, dared to criticize him, Mao said: “I now have a target,” and used the critic as a springboard to launch a terror campaign. Those who dared get in Mao’s way became the the way.

In a series of Politburo meetings in 1941, Mao made the CCP leadership condemn themselves and beg his forgiveness for their past transgressions. They were then made to swear loyalty to him. The meetings went well until one of the attendees showed his defiance. Wang Ming not only refused to criticize himself, but openly attacked Mao’s policies and challenged him to a public debate.

Underneath his cold and calculating façade, Mao was impulsive and passionate. He kept his passion contained under a heavy lid so well that he produced a convincing impression of absolute composure. In reply to a staff member who made a comment to Mao praising his level of self-control, Mao confessed: “It’s not that I am not angry. Sometimes I am so angry I feel my lungs are bursting. But I know I must control myself, and not show anything.”

Now, the lid was pushed aside and the steam burst forth. Mao was so furious that he wrote a number of articles condemning not just Wang Ming, but also others including Chou En-lai, former rivals who had since prostrated themselves before him. Mao could never forget or forgive. He called them “most pitiful little worms,” raging that “inside these people, there is not even half a real Marx, living Marx, fragrant Marx … there is nothing but fake Marx, dead Marx, stinking Marx.” He never ended up publishing them. The writing itself seemed to have provided enough catharsis for him to regain his self-control. But he did keep them. Like tiny fragments of his soul, these pages revealed the inextinguishable hatred burning in his heart. When in 1974 Wang Ming died in exile and Chou En-lai was suffering terminal cancer, Mao had these pages taken out of the archive and read to him (he was going blind). Two years later, a month before his death in 1976, he read them again. Like an inexhaustible source of fuel, his hatred for those who stood in his way seemed to provide him with the energy to fight until the very end.

A brief note on spelling. First, in Chinese names the surname goes first, so in places where I do not write the full name, I use the surname. Second, the book uses the Wade-Giles romanization system for Chinese names, which I follow as well, with the exception of Mao Zedong (spelled "Mao Tse-tung" in the Wade-Giles system), as this spelling is much more common.

As well as the quotes, all statistics used in this article are taken from the book ("Mao: The Unknown Story" by J. Chang and J. Halliday). Needless to say, they may differ from official CCP accounts.

A Russian term used by the Communists in a derogatory sense to describe wealthy peasants ("wealthy" being a very relative measure here). Stalin ordered the kulaks "to be liquidated as a class."