A Tyranny Without a Tyrant

Hannah Arendt’s essay On Violence offers a compelling perspective on the causes of unrest and violence, both from the side of the state and from the people.

Hannah Arendt’s On Violence was published over fifty years ago, but it might have been written today. Arendt’s essay was informed by two aspects of the political climate of her time. First, there was the Cold War and a very real prospect of nuclear annihilation. Second, there were a string of student rebellions taking place on campuses around the world. While the particulars differ, the fundamentals of these two things—at least with respect to the issues Arendt writes about—are essentially mirrored today with the threat posed by climate change and the rise in unrest and riots, particularly in the United States, but also in Europe and elsewhere. The conclusion Arendt arrives at in her essay is thus perhaps even more relevant today than at the time of its publication.

On Violence pulls together many of Arendt’s ideas from her other works, tying those ideas into a common thread that leads towards a compelling conclusion. To understand her conclusion we must therefore work our way through the thread. Arendt begins by examining the term itself. What is violence? And what makes violence different from other concepts such as power, strength, force and authority? Arendt defines the terms:

Power is the human capacity to act in concert. It is created by individuals coming together. “Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only as long as the group keeps together.” When somebody is “in power,” they are actually empowered by a group, and this position of power will cease to exist if the group is dissolved. Power is a “thing in itself,” which means that, unlike violence, it has no particular aim. Government “is essentially organized and institutionalized power.”

Strength is the physical capability of a single individual. Individual strength can always be overpowered by many. “It is in the nature of a group and its power to turn against independence, the property of individual strength.”

Force is the energy released by physical or social movement, e.g. the forces of nature.

Authority is unquestioned obedience without persuasion or coercion. Authority can be vested in individuals or offices and is present in certain relationships such as that between parent and child, or teacher and pupil. The moment coercion or persuasion are used, authority vanishes. “A father can lose his authority either by beating his child or by starting to argue with him, that is, either by behaving to him like a tyrant or by treating him as an equal.” Authority is predicated on respect. Contempt and ridicule are therefore the greatest enemies of authority.

Violence is strength multiplied by the use of implements. In its final stage, the use of implements completely substitutes for the use of strength, allowing one individual to coerce many others into obedience through the use of powerful tools and weapons. “Indeed one of the most obvious distinctions between power and violence is that power always stands in need of numbers, whereas violence up to a point can manage without them because it relies on implements. … The extreme form of power is All against One, the extreme form of violence is One against All.”

With these definitions in place, particularly that of power and violence, Arendt constructs an argument to explain the dynamic behind the student rebellion. The same conclusion can be used make sense of today’s wave of unrest.

We begin with the modern idea of “progress,” which, until modern times, did not even exist. History was cyclical, it had no beginning and no end. If it did have an end, it was the end of the world, the day of judgement. There was no movement from point A towards point B, there was no “improvement.” If anything, there was a fall from a golden age. Modern science brought with it many discoveries that have began reshaping the world, a world which until that point had experienced little fundamental change. Thinkers started to look history as a process. They saw humanity moving from a state that was “primitive” towards something more “advanced.” The idea of “progress” was born:

The notion that there is such a thing as progress of mankind as a whole was unknown prior to the seventeenth century, developed into a rather common opinion among the eighteenth-century hommes de lettres, and became an almost universally accepted dogma in the nineteenth. … Now, in the words of Proudhon, motion is “le fait primitif” and “the laws of movement alone are eternal.” This movement has neither beginning nor end: “Le movement est, voilà tout!” As to man, all we can say is “we are born perfectible, but we shall never be perfect.”

With the idea of “progress” came the idea of “growth.” How do we judge success in a world that is moving somewhere, that is making progress? We demand growth. We want science to keep creating new technologies, we want industry to keep producing more things. Our economy must keep growing. Should growth even begin to slow down, we scramble to think of ways to “stimulate” the economy, to make it grow faster.

To manage this growth, we have developed a new form of government called “bureaucracy,” a vast administrative apparatus which will only keep getting bigger as it has to manage our ever growing world. Unlike other forms of government, not only is a bureaucracy not representative—we don’t elect the bureaucrats—its size and structure eliminates individual responsibility. When everybody is responsible, no one is. It is rule by Nobody:

“… bureaucracy or the rule of an intricate system of bureaus in which no men, neither one nor the best, neither the few nor the many, can be held responsible, and which could be properly called rule by Nobody. (If, in accord with traditional political thought, we identify tyranny as government that is not held to give account of itself, rule by Nobody is clearly the most tyrannical of all, since there is no one left who could even be asked to answer for what is being done …)”

This is a problem because it takes away our ability to act. What is action? Arendt distinguishes “mere behavior” from action by suggesting that action must necessarily interrupt some ongoing process, it must create change. Simply following a process would lead to predictable results, and this would not be action. The function of bureaucracy, on the other hand, is to maintain the status quo, to maintain an ongoing process and minimize any disruption. In a way, it is the antithesis of action. Political freedom requires action, and by taking away our ability to act, our political freedom is also taken from us. As Pareto wrote: “freedom … by which I mean the power to act shrinks every day, save for criminals, in the so-called free and democratic countries.” Furthermore, the system cannot be argued with, because nobody is responsible:

In a fully developed bureaucracy there is nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one can present grievances, on whom the pressures of power can be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

And this is what in Arendt’s opinion was the likely cause of the student rebellions. By gathering together on campuses and on the streets, for the first time in their lives people feel power. They experience what it’s like to act in concert. Whether or not they are able to effect change, there is at least a sense of common action, a thing they have been completely deprived of:

I am inclined to think that much of the present glorification of violence is caused by severe frustration of the faculty of action in the modern world. It is simply true that riots in the ghettos and rebellions on the campuses make “people feel they are acting together in a way that they rarely can.”

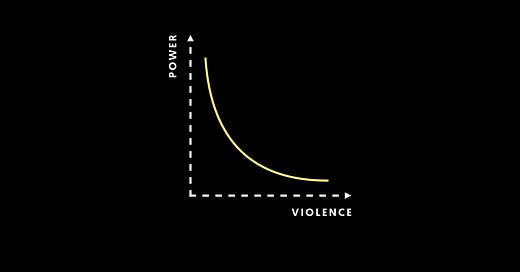

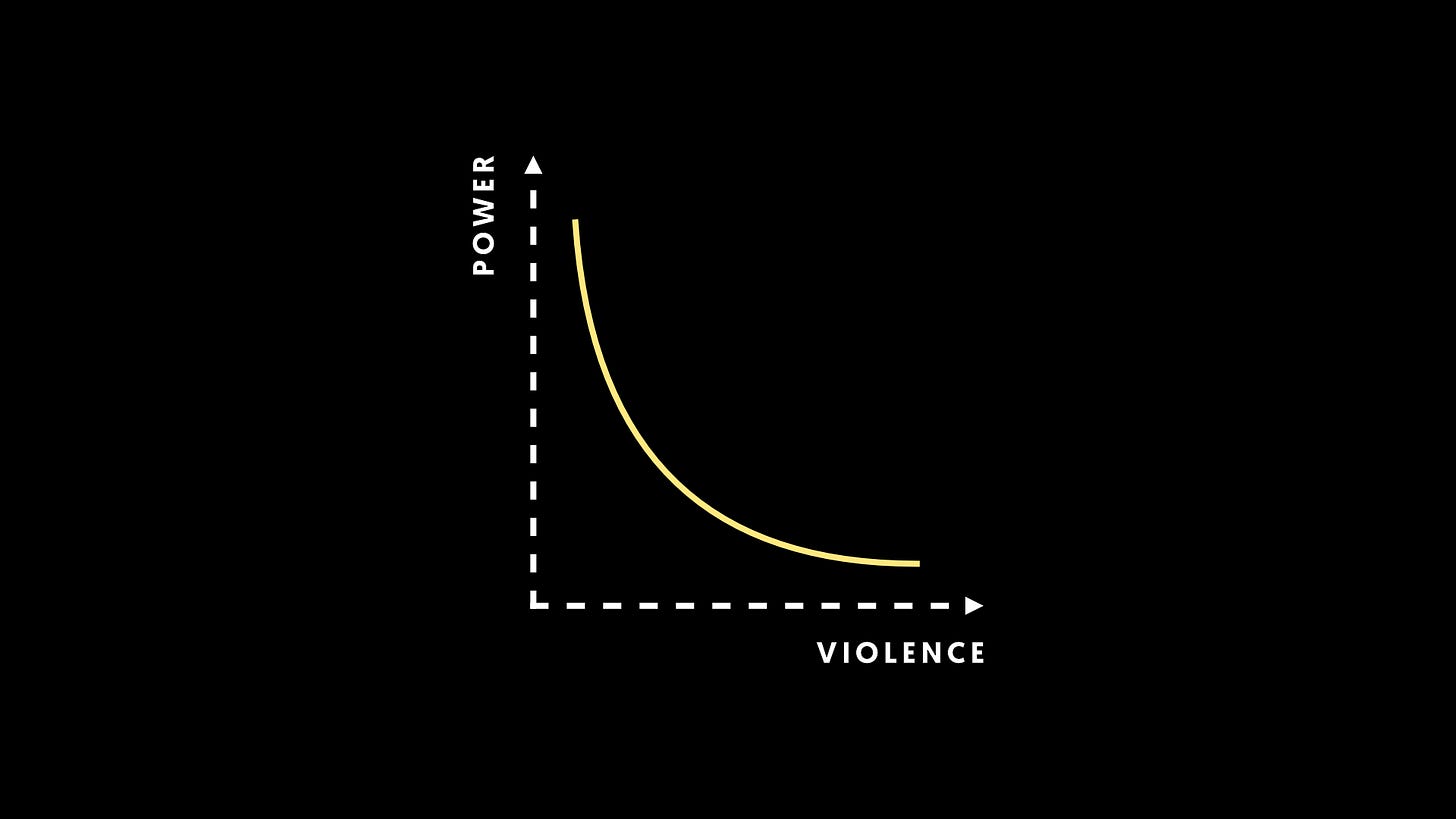

And violence? Violence is inversely related to power. “Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. … Violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it.” The more power you have, the less need you have for violence. As power slips away, violence is used by those who are losing it. At its final stage, when there is no power left at all, violence turns into terror, which is “the form of government that comes into being when violence, having destroyed all power, does not abdicate but, on the contrary, remains in full control.” Thus we see an explosion of violence, from any side that feels it is losing power. A failing state will use ever more violence to maintain control. The people, finding themselves in a world where action has been made impossible, will turn to riots.

Again, we do not know where these developments will lead us, but we know, or should know, that every decease in power is an open invitation to violence—if only because those who hold power and feel it slipping from their hands, be they the government or be they the governed, have always found it difficult to resist the temptation to substitute violence for it.