What Was Authority?

Hannah Arendt argues that not only has authority disappeared, but that we no longer even understand the meaning of the word. Furthermore, its disappearance leads to a loss of freedom.

It’s commonplace today to see oppressive or despotic regimes being referred to as “authoritarian.” This, according to Hannah Arendt, is a mistake. Not only is it the wrong term, but using it this way completely destroys its original meaning of authority and makes it impossible to even think about what it might have once meant. Last week I covered Arendt’s ideas on violence, which are as relevant today as they have been at the time of their publication. Today I’ll look at Arendt’s understanding of authority, which is perhaps even more important, and which gives us a very different lens through which to look at the trends in today’s world.

Arendt opens her essay What Is Authority? (published in Between Past and Future) by saying that it would have been more correct to ask: What wasauthority? For authority, as Arendt understands it, has vanished from the modern world.

Arendt’s conception of authority is based on a historical study of how the term was understood in the ancient world. More specifically, it is the Roman auctoritas that Arendt is interested in, from which the English word “authority” is derived. Unlike violence or persuasion, authority doesn’t require coercion or equality. It is, in the words of Mommsen, something “more than advice and less than a command, an advice which one may not safely ignore”:

Since authority always demands obedience; it is commonly mistaken for some form of power or violence. Yet authority precludes the use of external means of coercion; where force is used, authority has failed. Authority, on the other hand, is incompatible with persuasion, which presupposes equality and works through a process of argumentation. Where arguments are used, authority is left in abeyance. Against the egalitarian order of persuasion stands the authoritarian order, which is always hierarchical. If authority is to be defined at all, then, it must be in contradistinction to both coercion by force and persuasion through arguments.

The presence of a hierarchy gives rise to the confusion between authoritarian forms of government and tyrannies. It is assumed that the leader at the top of an authoritarian hierarchy wields ultimate authority, that it is this leader who issues commands and makes the laws for all the rest to follow. Arendt suggests that this is not at all the case. Where ultimate power rests with a single leader—the tyrant—we have a tyranny. In an authoritarian government, the leader is actually bound by laws that are above him, laws which he did not create and cannot change:

The difference between tyranny and authoritarian government has always been that the tyrant rules in accordance with his own will and interest, whereas even the most draconic authoritarian government is bound by laws. Its acts are tested by a code which was made either not by man at all, as in the case of the law of nature or God’s Commandments or the Platonic ideas, or at least not by those actually in power. The source of authority in authoritarian government is always a force external and superior to its own power; it is always this source, this external force which transcends the political realm, from which the authorities derive their “authority,” that is, their legitimacy, and against which their power can be checked.

To further highlight the difference between authoritarianism and tyranny, Arendt suggests the shapes that reflect the structure of each state. An authoritarian state can be imagined as a pyramid, with many intervening layers between the bottom base layer and the apex. At the top of the pyramid is the leader of the state, but, above him still, elevated over the pyramid, are the laws which govern his actions. These laws are not a part of the power structure, they lie outside of it.

A tyranny is a little like authoritarianism, except all the intervening layers of the pyramid have been taken out. What we have left is the base layer, which is the people, and the apex, which is the tyrant and his bodyguard. Unlike authoritarianism, which has many classes, a tyranny is a purely egalitarian society in which everyone, except the tyrant, has been made equal.

Lastly, Arendt imagines the shape of totalitarianism. Totalitarianism can be seen as an onion, with multiple layers going in towards the center, where we find the leader. The reason totalitarianism is not a pyramid is because each layer must be isolated from all the others, except for the two that directly interact with it. The ideological content of the layers increases as its members move towards the center, that is, the message becomes ever more radical as the members progress into the inner circles. This makes these members feel special by thinking that they are becoming privy to some secrets the outside layers do not possess, while at the same time concealing from the outside world just how extreme a totalitarian party’s ideology actually is.

But what exactly is authority? Authority goes back to the Romans—the Greeks had no conception of authority. Authority is closely related to augmentation:

The word auctoritas derives from the verb augere, “augment,” and what authority or those in authority constantly augment is the foundation. Those endowed with authority were the elders, the Senate or the patres, who had obtained it by descent and by transmission (tradition) from those who had laid the foundations for all things to come, the ancestors, whom the Romans therefore called the maiores. The authority of the living was always derivative, depending upon the auctores imperii Romani conditoresque, as Pliny puts it, upon the authority of the founders, who no longer were among the living.

The word auctor means much the same as the English “author.” An authority is, in a sense, the “author” of something, the one who creates the original design that is then constructed by others. With regards to a state, the ancestors are an authority who have created a foundation upon which the state grows and is “augmented” by the future generations. They are what’s known as the “founding fathers.” Those among the living who have authority, such as the elders and the Senate, don’t actually have power (Cum potestas in populo auctoritas in senatu sit: “While power resides in the people, authority rests with the Senate”). What they do have is the authority to give a type of advice that needs “neither the form of command nor external coercion to make itself heard.” They act as the bridge between the present and the past, connecting current actions to the state’s foundations. The ability to bear the weight of the past stretching back to the foundation of Rome is what was known as gravitas.

This is why, unlike the Greeks, the Romans have built their empire around a single city. Whenever the population of a Greek city would grow too large, settlers would sail off to found new colonies (“Go and found a new city, for wherever you are you will always be a polis.”) Romans, however, were “rooted in the soil.” Rome was a foundation that could not be moved, it could only be “augmented.” The empire could only spread and grow outwards, “as though the whole world were nothing but Roman hinterland.”

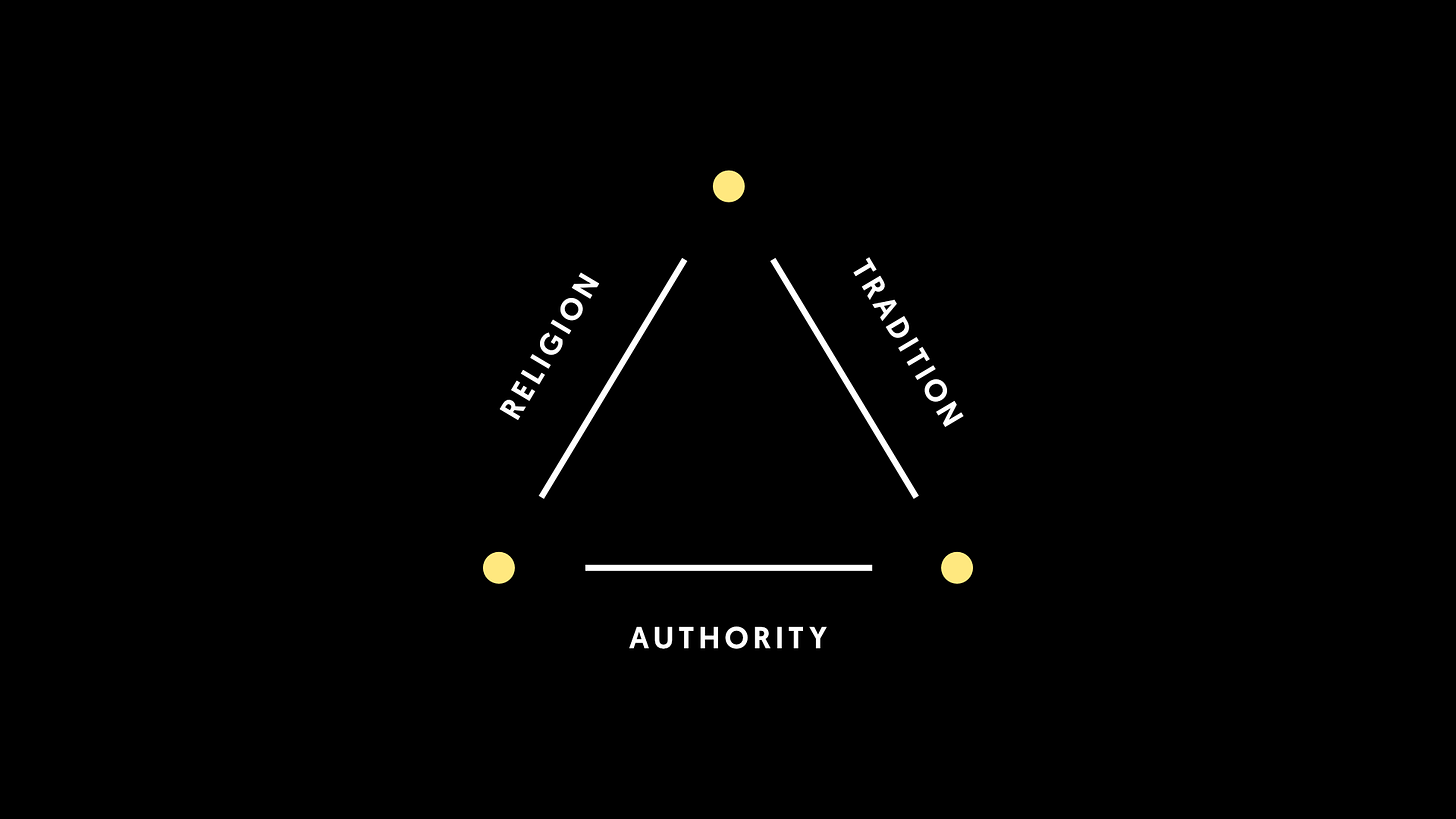

The existence of authority is closely linked to two other phenomena, religion and tradition, which, taken together, form the Roman trinity. The Roman conception of religion literally meant religare, “to be tied back, obligated, to the enormous, almost superhuman and hence always legendary effort to lay the foundations, to build the cornerstone, to found for eternity.” Tradition was the bond that tied men back to the past.

The Roman trinity has survived the advent of Christianity, and, in a way, moulded it after its own image:

… the Church became so “Roman” and adapted itself so thoroughly to Roman thinking in matters of politics that it made the death and resurrection of Christ the cornerstone of a new foundation, erecting on it a new human institution of tremendous durability. … As witnesses to this event the Apostles could become the “founding fathers” of the Church from whom she would derive her own authority as long as she handed down their testimony by way of tradition from generation to generation.

As time went on, Christianity introduced an element of violence in the form of the concept of a heaven and hell—a system of punishments and rewards to get the masses, who could not be persuaded by reason, to obey its doctrines. This corrupted the pure authority of its founders and, while effective at first, turned out to be counterproductive. As the ideas of heaven and hell grew doubtful, the threat became less convincing, and with it, the Church began to lose its authority. And, because the elements of the Roman trinity as so closely tied together, as any one of them fall, the rest follow:

… wherever one of the elements of the Roman trinity, religion or authority or tradition, was doubted or eliminated, the remaining two were no longer secure. Thus, it was Luther’s error to think that his challenge of the temporal authority of the Church and his appeal to unguided individual judgement would leave tradition and religion intact. So it was the error of Hobbes and the political theorists of the seventeenth century to hope that authority and religion could be saved without tradition. So, too, was it finally the error of the humanists to think it would be possible to remain within an unbroken tradition of Western civilization without religion and without authority.

Why does this matter? While it’s true that tradition is not the same thing as the past, and that religions change, their loss results in some serious consequences. First, if Arendt is correct, then the loss of authority also means the loss of tradition, and with the loss of tradition, the remembrance of the past and the loss of a “dimension of depth in human existence”:

We are in danger of forgetting, and such an oblivion—quite apart from the contents themselves that could be lost—would mean that, humanly speaking, we would deprive ourselves of one dimension, the dimension of depth in human existence. For memory and depth are the same, or rather, depth cannot be reached by man except through remembrance.

Perhaps more important, the loss of authority goes hand in hand with the loss of freedom:

Liberalism, we saw, measures a process of receding freedom, and conservatism measures a process of receding authority; both call the expected end-result totalitarianism and see totalitarian trends wherever either one or the other is present. … If we look upon the conflicting statements of conservatives and liberals with impartial eyes, we can easily see that the truth is equally distributed between them and that we are in fact confronted with a simultaneous recession of both freedom and authority in the modern world.

The reason for this is clear. Authority is what gives rise to a stable, political foundation upon which we move and act, it is the force that maintains boundaries and laws that place limits upon the actions of those in power. These limits are the source of our freedom. The American Revolution, with its “founding fathers” and its Constitution and its Senate is perhaps the last example of a successful authoritarian government (inspired, unsurprisingly, in large part by the Roman model). It is that hallowed “foundation” that ensures the stability of the civil freedoms granted by Constitution. With the loss of authority, the Constitution becomes yet another set of laws, to be changed and amended at whim. With the loss of authority, it is no longer stable and secure, and, in turn, neither are the freedoms provided by it.