The 1 Mindset Switch You Need to Make to Achieve Consistent Success

Carol Dweck suggests that how we react to success or failure is governed by one of two mindsets. One leads to anger, deceit, and ruin, the other allows us use failure to grow and succeed.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he rushed to make significant changes to save the company that was then on the verge of death. He had to pick a direction to pursue, which also meant deciding on what directions not to pursue—thus causing potential disappointment to some people. Responding to a vocal critic at a conference, Jobs said:1

Some mistakes will be made along the way. That’s good. Because at least some decisions are being made along the way. And we’ll find the mistakes. We’ll fix them.

As Seth Godin writes, “All forward motion disappoints someone. If you serve one audience, you’ve let another down. One focus means that something else got ignored.” If we try to avoid mistakes or negative judgement by avoiding making important decisions then we’ll never get anywhere. Mistakes can be fixed. Direction can be altered. What’s fatal is indecision and immobility.

Sara Blakely, the founder of Spanx, whose net worth in 2020 was over half a billion dollars,2 credits a large portion of her success to a lesson her father taught her. Every evening, Blakely’s father would ask her: “What did you fail at today?” And if she couldn’t give him an answer he would be disappointed. Blakely says that this changed the way she thought about failure, so “instead of failure being the outcome, failure became not trying.”3

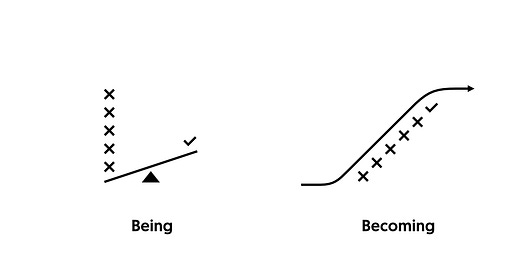

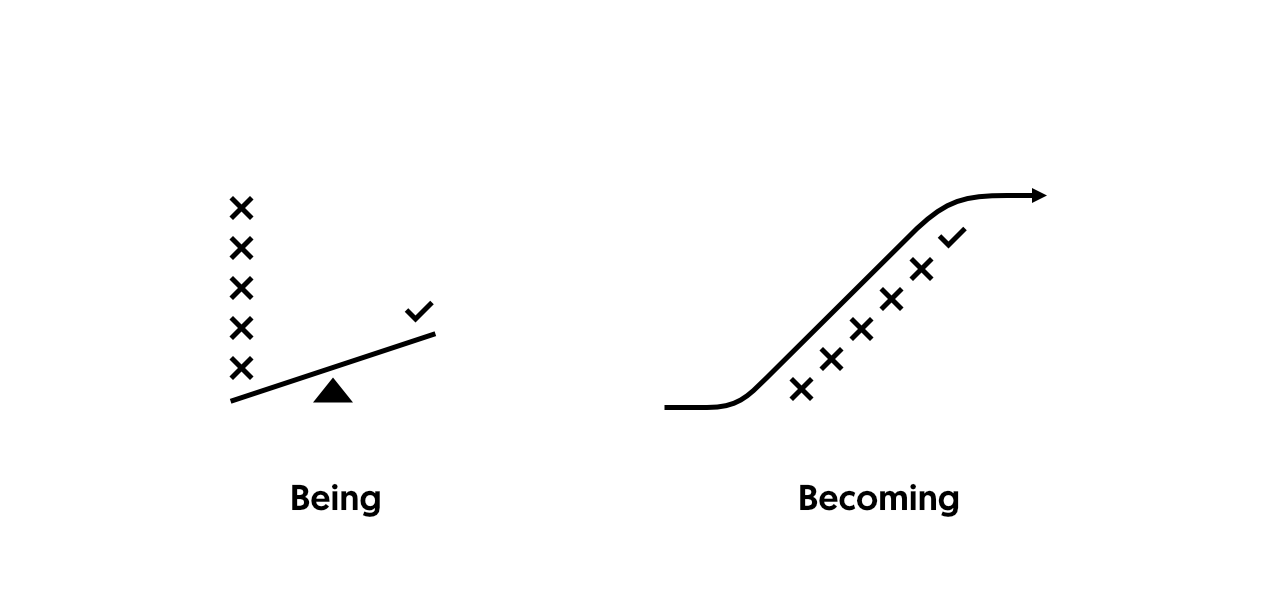

Growth vs Fixed Mindset

Carol S. Dweck captured the distinction between two ways of viewing failure in her book Mindset.

Benjamin Barber, an eminent sociologist, once said, “I don’t divide the world into the weak and the strong, or the successes and the failures. … I divide the world into the learners and nonlearners.”

Dweck uses the terms “growth” and “fixed” mindset to describe the learners and nonlearners.

Those in a growth mindset see challenges as opportunities to grow, and mistakes and failures as lessons on their path to improvement. If someone is rude to them, their first reaction is not to take offense, but wonder why that person might be acting the way they are, whether something is wrong with them. If they are having trouble adjusting to a promotion, their first reaction is not to get depressed and feel that they’re not worthy, but to seek out others with more experience than them and ask them for help. A growth mindset believes that every challenge can be overcome. They just need to figure out what needs to be done, and then do it.

Those in a fixed mindset see failure as an identity, i.e. “I’m a failure,” rather than an action, “I failed.” To a fixed mindset challenges are to be avoided because the potential of failure threatens their ego. It’s the distinction between learning and appearing smart, between doing and taking credit. A fixed mindset believes in innate talent, and that some people are just better at certain things than others. Those in a fixed mindset may achieve success, but that success will only inflate their ego, making it ever harder for them to take subsequent risks. Failure takes a heavy toll on their emotions because their self-worth is linked to the successful outcome of their actions.

The mindset we are in governs the way we approach challenges and setbacks. A study of 7th graders showed that after failing a test, those in a growth mindset decided to study harder for the next one, but those in a fixed mindset got discouraged and even admitted that they considered cheating. As Dweck writes, “If you don’t have the ability, they thought, you just have to look for another way.”

This effect is present in every pursuit, whether it’s education, business, or sports. For example, Dweck cites Malcolm Gladwell on how the culture at Enron laid the foundation for its collapse:

Enron recruited big talent … But by putting complete faith in talent, Enron did a fatal thing: It created a culture that worshiped talent, thereby forcing its employees to look and act extraordinarily talented. Basically, it forced them into the fixed mindset … Gladwell concludes that when people live in an environment that esteems them for their innate talent, they have grave difficulty when their image is threatened: ‘They will not take the remedial course. They will not stand up to investors and the public and admit that they were wrong. They’d sooner lie.’

Or, as Ryan Holiday puts it in Ego Is the Enemy: “He who will do anything to avoid failure will almost certainly do something worthy of a failure.”4

Switch to a growth mindset

Mindsets are not permanent, they are simply a mental state we are in at a moment in time. Moreover, it is not the case that we are either one or the other, that we are either in a growth mindset or in a fixed mindset. For certain things, at certain times, we may be in a growth mindset, and fixed for others. Our experiences and the way we are treated by others may push us into one or the other state.

The key step to switching our mindset to a growth one is to become aware of how we react to things like challenges, effort, feedback and failure. Once we catch ourselves reacting negatively, we can think of a constructive action we can take. And, as Dweck writes, we don’t have to feel good about failure to do the right thing: “You can feel miserable and still reach out for information that will help you improve.”

For example, a student applied to a graduate school she really wanted to get into. She applied to just one school because she believed she could make it. But she was rejected. What did she do? The fixed mindset would have her depressed and questioning her self-worth—maybe she just isn’t good enough?

She was given growth mindset advice, and this is what she did: she called the school and asked to speak to the person responsible for admissions. She explained that she was rejected, but, because she was interested in applying again in the future, she wanted to know the reasons she failed so that she would know what she needed to improve.

They explained that it was a close call, and then… they actually changed their mind and decided to accept her, saying that they really liked her initiative. By reframing her rejection from a “failure” to a step in the process of getting where she wanted to be, she took the steps she needed to take to move forward and actually achieved the outcome. And even if she wasn’t accepted right then, she could still have gotten valuable feedback to help her in the future.

At the end of the book Dweck gives us a list of the main characteristics of the two mindsets to help us recognize which one we are in so that we can reorient ourselves:

Fixed mindset:

Avoid challenges

Get defensive or give up easily

See effort as fruitless or worse

Ignore useful negative feedback

Feel threatened by the success of others

Growth mindset:

Embrace challenges

Persist in the face of setbacks

See effort as the path to mastery

Learn from criticism

Find lessons and inspiration in the success of others

The Path to Mastery

Understanding the role of failure in growing is crucial if we wish to achieve anything great. Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the most talented and creative philosophers of the 19th century, saw the path to mastery as a long road of learning and laboring, a gradual process of mastering every little piece of one’s craft before “daring” to create a larger, more ambitious whole:5

Speak not of gifts, or innate talents! One can name all kinds of great men who were not very gifted. But they acquired greatness, became “geniuses” (as we say) through qualities about whose lack no man aware of them likes to speak; all of them had that diligent seriousness of a craftsman, learning first to form the parts perfectly before daring to make a great whole. They took time for it, because they had more pleasure in making well something little or less important, than in the effect of a dazzling whole.

In Mastery, Robert Greene splits the path to excelling in your field into 3 stages: apprenticeship, creative-active, and mastery. In the apprenticeship phase we must learn from others, imitating them until we start to grasp the essentials of our craft. In the creative-active phase we begin to experiment. It’s impossible to fail at this stage because our failures are the path of our growth. Eventually, we gather so much experience within our subconscious mind that we begin to make intuitive connections. We begin to master our craft.

Thus, even if your ultimate ambitions are grand, the staircase to achieving them is long, with many steps, and the steps themselves can be very small. By taking pleasure in “making well something little or less important” we slowly begin to master the skills required to construct a larger whole. By disconnecting our ego from the outcome and viewing failure as a vehicle for growth, we can begin see it in a positive light, judging it better to fail at something today than to not even try.

Steve Jobs responding to criticism at the 1997 WWDC (video clip)

From an ABC News interview quoted in: 99U, If You’re Not Failing, You’re Not Growing

Inspired by Seneca: “He who fears death will never do anything worthy of a living man”

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human (163: “The seriousness of craft”)