At the Pharmacy

By Anton Chekhov. First published in The Petersburg Gazette, 1885, subtitled “A little scene.”

It was late evening. Private tutor Yegor Alekseich Svoikin went straight to the pharmacy after his doctor’s visit so as to not waste any time.

“It’s as if I’m going to visit a wealthy mistress or a railwayman,” he mused as he climbed the pharmacy staircase, shiny and carpeted with expensive rugs. “I’m scared to even step on it!”

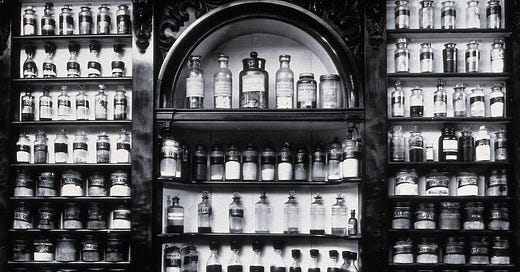

As he entered the pharmacy, Svoikin was seized by a smell inherent to all the pharmacies in the world. Science and medicine change with the years, but the smell of a pharmacy is eternal, like matter. Our grandfathers smelled it, and our grandchildren will smell it. Thanks to the late hour, there were no other people at the pharmacy. Behind a shiny yellow desk, covered with little labelled vases, stood a tall gentleman with his head respectably thrown back, a stern face and well-groomed sideburns—by all appearances, the pharmacist. Starting with the little bald patch on his head and ending with the long pink nails, everything on this man was diligently ironed, cleaned and polished, enough to go down the aisle. His frowning eyes gazed down from above onto a newspaper that was lying on the desk. He was reading. On the side behind a grille sat the cashier, lazily counting small change. On the side of the counter that separated the Latin kitchen from the crowd, two dark figures were pottering about. Svoikin approached the desk and gave the prescription to the ironed gentleman. The other, without looking at him, picked up the prescription, finished reading his newspaper by reaching a full stop and, turning his head slightly to the right, mumbled:

“Calomeli grana duo, sacchari albi grana quinque, numero decem!”1

“Ja!”2 sounded a sharp, metallic voice from the depth of the pharmacy.

The pharmacist dictated the mixture in the same dull, measured voice.

“Ja!” sounded a voice from another corner.

The pharmacist wrote something on the prescription, frowned and, throwing back his head, looked down at the newspaper.

“It’ll be ready in an hour,” he strained through his teeth, searching with his eyes for the full stop at which he had stopped.

“Any chance you could do it sooner?” mumbled Svoikin. “It’s decidedly impossible for me to wait.”

The pharmacist made no reply. Svoikin lowered himself onto a sofa and began to wait. The cashier finished counting the small change, took a deep breath and clicked with his key. In the depth, one of the dark figures stirred by a marble mortar. The other figure was shaking something in a blue bottle. Somewhere a clock was beating measuredly and carefully.

Svoikin was ill. His mouth was burning, he felt a constant dragging pain in his legs and arms, hazy images wandered in his heavied head… brokenness and brain fog were overcoming his body more and more, and so, having waited a little and feeling that the knocking of the marble mortar was making him nauseous, he decided, to cheer himself up, to talk with the pharmacist…

“I must be getting a fever,” he said. “The doctor said that it’s still difficult to say what disease I have, but I’ve grown so tired… Still, I’m lucky that I’ve fallen ill in the capital, God forbid this thing strikes one in a village, where there are no doctors and pharmacies!”

The pharmacist stood motionless with his head thrown back, reading. To Svoikin’s address he replied neither with word, nor movement, as if he did not hear him… The cashier yawned loudly and struck a match against his trousers… The knocking of the marble mortar was growing louder and more sonorous. Seeing that they were not listening to him, Svoikin looked up at the shelves with some jars and began reading the labels… At first all manner of “radixes” flashed before him: gentiana, pimpinella, tormentilla, zedoaria, etc. After the radixes flashed the tinctures, olea, semina, each with a name more antediluvian and convoluted than the last.

“There must be so much useless ballast here!” thought Svoikin. “There’s so much inertia in these jars, which are only here because of tradition, and yet how respectable and imposing it all is!”

From the shelves Svoikin shifted his eyes to a glass étagère standing near him. Here he saw rubber rings, balls, syringes, little jars with toothpaste, Pierrot drops, Adelheim drops, cosmetic soaps, a hair growth ointment…

A lad in a dirty apron entered the pharmacy and asked for 10 kopeks’ worth of ox bile.

“Tell me, please, what is ox bile used for?” the tutor addressed the pharmacist, happy to have something to talk about.

Receiving no answer to his question, Svoikin began examining the stern, haughtily-learned physiognomy of the pharmacist.

“By God! These people are strange,” he thought. “What are they putting on the learned airs for? They fleece their neighbor, they sell hair growth ointments, and looking at their faces one might think that they really are priests of science. They write in Latin, they speak in German… They try to put on something medieval… In a healthy state you don’t notice these dry, callous physiognomies, but when you fall ill, like I am now, then you’re horrified that a sacred task had fallen into the hands of this unfeeling, ironed figure…”

As he was examining the motionless physiognomy of the pharmacist, Svoikin suddenly felt a desire to lie down, no matter what, away from the light, from the learned physiognomy and the knocking of the marble mortar… A painful fatigue had taken over the whole of his being… He approached the desk and, putting on a pleading grimace, asked:

“Please be so kind and let me leave! I’m… I’m ill…”

“In a moment… No leaning please!”

The tutor sat down on the sofa and, chasing away the foggy images from his head, began looking at the way the cashier was smoking.

“Only half an hour had passed,” he thought. “Just as much left to go… It’s unbearable!”

But, finally, a little dark-haired man approached the pharmacist and placed a box with the powders and a bottle with a pink liquid next to him… The pharmacist finished reading to a full stop, slowly moved away from the desk and, having picked up the vial, dangled it a little before his eyes… Then he wrote his signature, tied it to the neck of the bottle and reached for the stamp…

“What’s the use of these ceremonies?” thought Svoikin. “A waste of time, and they’re even going to charge me for this.”

Having wrapped, tied and stamped the mixture, the pharmacist proceeded to do the same with the powders.

“Here you are!” he finally uttered without looking at Svoikin. “Pay the cashier a ruble and six kopeks!”

Svoikin reached into his pocket for the money, took out a ruble and at once remembered that apart from this ruble he did not have a single kopek more…

“A ruble and six kopeks?” he mumbled, growing embarrassed. “But I only have a ruble… I thought that a ruble would be enough… What’s to be done?”

“Don’t know!” rapped out the pharmacist as he took up the newspaper.

“In that case I’m sorry but… I’ll bring you the six kopeks tomorrow, or send them…”

“Impossible… we don’t offer credit…”

“But what should I do?”

“Go home, bring the six kopeks, and you’ll get your medicine.”

“Perhaps, but… It’s difficult for me to walk, and I have nobody to send…”

“Don’t know… none of my business…”

“Hmm…” thought the tutor. “Alright, I’ll go home…”

Svoikin exited the pharmacy and set off home… Before he reached his apartment he had to sit down to rest about five times… Coming to himself and having found a few copper coins in the desk, he sat down on the bed to rest… Some force pulled his head towards the pillow… He lay down, as if for a minute… Hazy images of clouds and shrouded figures began to darken his consciousness… For a long time he remembered that he had to go to the pharmacist, for a long time he tried to force himself to get up, but the illness took its toll. The coppers fell out of his fist, and the sick man dreamed that he was already walking to the pharmacy and was again speaking with the pharmacist.

Two grains of Calomel, five grains of sugar, ten powders! (Latin)

Yes! (German)